The 19th Century Pharmacy

Medicinal herbs are a force of nature created for all living beings

A small door, narrow and camouflaged, separates the Cell of Poisons from the pharmacy; symbol of the limit of what is allowed for laypeople, protects the inaccessibility of places in which secretly materializes the knowledge of the pharmacist.

Stand at the centre bench, where the apothecary wrote and prepared medicines using the practical wooden removable support.

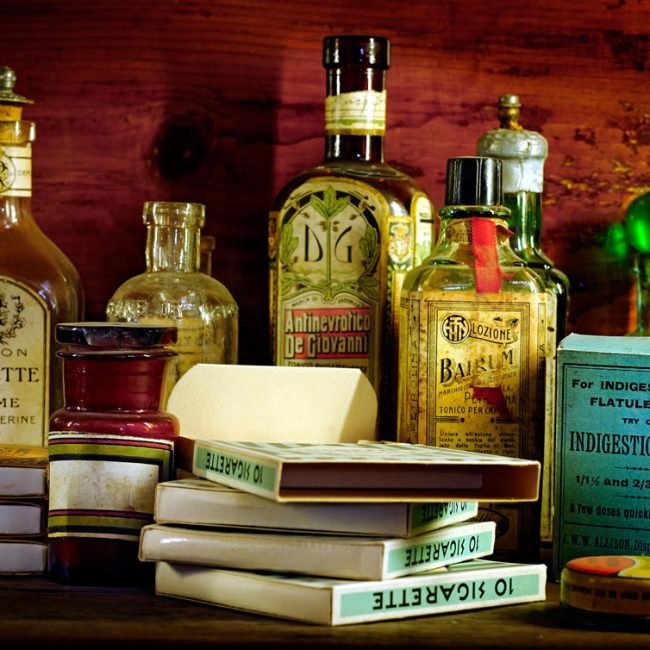

The three walls that surround you are those of an authentic 19th century pharmacy, rebuilt with pine furniture and furnishings.

Inside the cabinets, the medicines are carefully stored in medicine containers of the period: a chromatic succession of boxes, containers, ceramics and vessels. Above, hang an embalmed crocodile and a turtle’s carapace, which respectively symbolise plant fertility and the compassion of animals towards humans.

Two phrases placed up high bid farewell to the visitor, with clear intentions: an invitation to reflect on the future of man and the need for a commitment to research and study in the field of medical botany.

Historical – Phylosophical Extension

In the Pharmacy, the public space was generally divided by the laboratory through a little and narrow door, sometimes artistically camouflaged between the shelves for medicines.

For profanes it symbolised the limit of what is allowed and accessible to everybody, it protects the inaccessibility of spaces that are invested by an aura of mistery and extraordinary, where the knowledge of the pharmacist is secretly materialized.

In professional or academic corporations, a door always separated the ordinary space from the special space reserved for affiliates. In these cases the door is narrow, to remember the difficulty of reaching knowledge. Beyond the door, the places are exclusive, accessible only to the wise: science – and sciences – affirm there their own domain.

The remains of a crocodile and a turtle are often present in ancient pharmacies.

Simbolically, the crocodile is connected with water and lush vegetation: in synthesis, with plant fertility. In Egypt he was considered the master of the mysteries of life and death. In the mythology of the Maya, the head of the crocodile gave rise to plants useful to man. The animal was considered effective against many diseases, as remembered in an Egyptian papyrus of 1600 BC. Another papyrus of 1200 BC handed down a magic-therapeutic ritual for the headache: a phytonuclear crocodile with healthy herbs in the mouth is tied on the head of the patient. In antiquity, the medicinal products derived from crocodiles were also credited with aphrodisiac properties. This belief still survives in Egypt.

The therapeutic use of the turtle shell is attested in China since the third century B.C. and continues today. In the oldest Chinese books of medicine, turtle shell is a basic raw material of animal origin – along with deer horns. According to the Taoist tradition, the gelatin obtained from it balanced the vital principles of the organism, Yin and Yang. The healing properties of the carapace, finally, symbolized the compassion of animals for human health.