The Phytochemical Laboratory

The 18th century is a time of transition

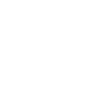

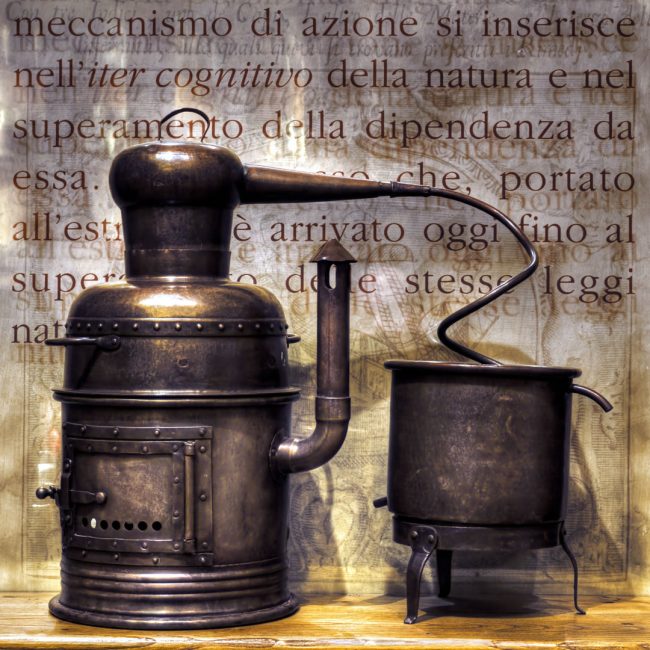

All’interno del laboratorio si può vedere come gli strumenti di lavoro siano cambiati per adeguarsi alle nuove scoperte: non più voluminosi strumenti per la trasformazione chimica degli ingredienti, ma delicate bilance, distillatori e vasi in vetro, perché al farmacista restava sostanzialmente il compito di analizzare e confezionare le ricette magistrali.

È tra il 1700 e il 1800 che si scoprono numerosi principi attivi vegetali: il chinino, la caffeina, la morfina, la codeina e la salicina.

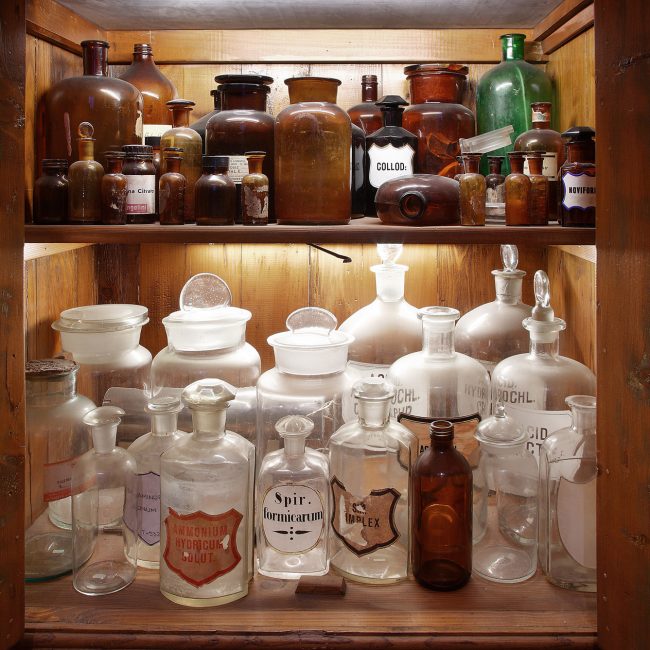

Dall’isolamento di questi e altri principi attivi vegetali si esplica la volontà dell’uomo di gestire i meccanismi di azione delle piante, nel desiderio di superare la dipendenza dalla natura.

“Nothing is created, nothing is lost, but everything changes”.

This one sentence contains the dogmas of the development of the chemistry of natural substances, which began at the end of the 18th century in the work of the French scientist Antoine Laurent Lavoisier.

Inside the laboratory you can see how the working tools have changed to adapt to new discoveries: no more the bulky tools for the chemical transformation of ingredients, but delicate scales, distillers and glass jars, because the pharmacist largely kept the task of analysing and packaging the recipes requiring such skill.

It is between 18th and 19th century that many active plant ingredients are discovered: quinine, caffeine, morphine, codeine and salicin.

From the isolation of these and other active plant ingredients, man directs his attention to managing the mechanisms of action of plants, in a desire to overcome his dependence from nature.

Historical – Phylosophical Extension

The end of the 18th century was marked by the work of the French scientist Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743-1794), who, having rejected the theory of phlogistics, laid the foundations of modern chemistry.

A series of discoveries changed the face of 19th-century pharmaceutics: among the many vegetal active ingredients were quinine, caffeine, morphine, codeine, salicin (the base of aspirin), and the new synthesised inorganic products that included chloroform, iodine, bromine and magnesium citrate.

Pharmacists’ workshops manufactured products derived essentially from pharmaceutical chemistry: the medicinal ingredients were prepared on a large scale by industrial laboratories and reached the pharmacists’ shops via wholesale distribution. The range of tasks undertaken by pharmacists was substantially restricted, since they were left with the analysis and control of medicines and with the preparation of prescriptions.

They made up pastilles, pills, granulated products, syrups, ointments, medicated oils, pomades and tinctures. This change was reflected in the pharmacist’s laboratory: the tools used for chemical transformation diminished in number and were replaced by tools used for mechanical processing; pots and containers became standardised and lost their distinctive appearances, and labels were reprinted in large numbers.Phytochemical laboratory symbolizes the man’s intellectual and existential suffering, obsessed from the idea to dominate nature and its chemical-physical laws. It is the result, therefore, not just of the phylosophical presumptuousness to succeed possessing the mechanismes that regulate living organisms’ life, but also of the summary of experiences more and more sophisticated which are led in the matter, from alchemic and iatrochemical derivation, with the intention to reveal the “secret” of remedies’ property.

In particular, as far as the medicinal plants, the isolation of active principles and the possibility to manage their mechanism of action become part in the cognitive iter of nature and to the dependency from it. A process that, carried to the end, has arrived today until the overcoming of the same natural laws.